The Philosophy of Franz Kafka: A Quiet Revolt Against Modern Society

Franz Kafka does not shout. He whispers. But his whisper is unsettling. It echoes across corridors without end, across courts without justice, across lives that cannot quite wake from a dream that isn’t theirs. In Kafka’s world, meaning is not given. It is searched for—desperately, absurdly, and sometimes hopelessly.

He writes not to explain the world, but to confess the haunting strangeness of being in it. His philosophy is not systematic. It is felt, like a tremor in the chest. He does not provide doctrines. He offers silence, questions, and the suffocating weight of existence. And in that quiet darkness, Kafka invites us to face ourselves.

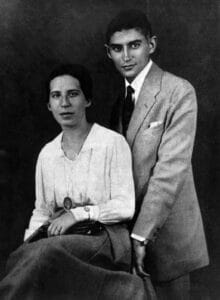

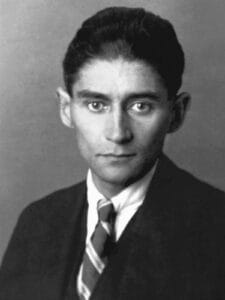

Born Into Shadows: Kafka’s Life and the Formation of His Thought

Kafka was born in 1883 in Prague, into a German-speaking Jewish family under the Austro-Hungarian Empire. That alone placed him on the margins. He belonged everywhere and nowhere. Jewish among Christians. German among Czechs. Modern among the ancient. His life was a lesson in displacement, a slow unfolding of what it means to exist without a true home.

His father, Hermann Kafka, was large, loud, and imposing. Kafka, frail and introspective, could never measure up. In his now-famous Letter to His Father, Kafka wrote, “I was crushed under the weight of your personality.” He tried to love him. He tried to resist him. Neither worked. This lifelong wound—of being small in a world too large, too loud—bled into every word he wrote.

Kafka studied law to please his family but loathed the bureaucracy. He worked in an insurance office by day and wrote by night. Alone. Secretly. Most of his works remained unpublished in his lifetime. He instructed his friend Max Brod to burn them after his death. Brod disobeyed. And so Kafka lived in obscurity but became immortal.

If there is one feeling that defines Kafka’s world, it is alienation. Not dramatic loneliness—but the quiet, chronic dislocation of existing without belonging. In The Metamorphosis, Gregor Samsa wakes up as a giant insect. No one asks how it happened. No one tries to understand. His family is horrified, not by the absurdity of his condition, but by the inconvenience of it.

Gregor is not hated. He is simply no longer useful. And in Kafka’s vision, that is worse than hatred. It is indifference. Kafka saw modern life as a machine that devours intimacy, questions, even identity. One is no longer seen. One is processed.

He wrote, “I am a cage, in search of a bird.” That is alienation. The feeling of being empty, but not by accident—by design. The modern self, in Kafka’s eyes, is something slowly rubbed out by routine, by expectation, by institutions too vast to even face directly.

The Absurd Authority: Bureaucracy and the Incomprehensible Power

In The Trial, Josef K. is arrested one morning for a crime he does not know. He never finds out what he’s charged with. He never learns who the judges are. He is trapped in a system of perpetual delay, undefined rules, and silent rooms. He says, “Someone must have slandered Josef K., for one morning, without having done anything wrong, he was arrested.”

Kafka understood something chilling about the modern condition. We are ruled by systems we do not understand. Bureaucracy, law, government, even religion—these institutions once promised meaning. Kafka shows us how they now offer only procedure.

The real horror is not in cruelty. It is in opacity. No one explains. No one listens. The trial continues endlessly. Josef K.’s real trial is not legal. It is existential. It is the trial of being born into a world where judgment is everywhere, but justice is nowhere.

Though Kafka rarely wrote directly about theology, his work is saturated with spiritual ache. He grew up in a Jewish household but was never devout. Still, he could not let go of the hunger for God. Many of his parables carry a biblical gravity—but twisted, unfinished, veiled.

In his short story Before the Law, a man seeks access to a mysterious gate of justice. He waits his entire life. He is never allowed in. At the end, the gatekeeper says, “This door was intended only for you. Now I am going to shut it.”

It is a parable of longing. Kafka’s God is not absent, but unreachable. We knock. We wait. But the door never opens. The silence is louder than rejection. And yet Kafka never becomes a nihilist. He never stops knocking. In one of his notebooks, he writes, “The Messiah will come only when he is no longer necessary.” That is Kafka’s theology. Faith without reward. Hope without comfort.

He lived in the gap between yearning and arrival. Between prayer and silence. In that painful space, he found the shape of modern spiritual life.

Transformation and Identity: The Fragile Boundary of the Self

Kafka’s stories often begin with transformation—not triumphant or magical, but silent and irreversible. The self does not evolve. It slips away. In The Metamorphosis, Gregor does not fight his transformation. He accepts it. As though it was always waiting to happen.

Kafka’s characters are constantly being renamed, misnamed, erased. In The Castle, K. is summoned by a distant authority to a village. But no one knows why he’s there. No one gives him answers. The more he tries to assert who he is, the more the world denies him.

For Kafka, identity is not stable. It is questioned, fragmented, dissolved. The world does not destroy the self. It ignores it until it fades. The tragedy is not in confrontation. It is in being forgotten. Being overlooked until one doubts one’s own name.

Love in Kafka: A Distant and Broken Mirror

Kafka loved deeply but lived in constant fear of intimacy. His letters to Felice Bauer, his fiancée, are filled with yearning and terror. He writes to her not like a man in love, but like a man under trial. “I cannot live with you. I cannot live without you,” he says. Love, for Kafka, was another system he could not master.

In Letters to Milena, his correspondence with Milena Jesenská, we see a man burning with affection and shame. He yearned for a connection that would not consume him—but love, like life, demanded a surrender he could not offer.

Kafka feared that in loving, he would vanish. That intimacy would reveal him as empty. So even in love, he remained behind a glass wall. Close to something sacred, but never allowed in.

The Burden of Being

Kafka lived not with answers, but with questions that never ceased whispering at the edges of consciousness. He searched for truth, not in grand systems or ideologies, but in the quiet moments of despair. He never shouted. He never claimed to know. Yet, in the silence of his characters, in their haunting solitude, we hear the profound struggle of a man trying to make peace with existence.

Few writers have captured the feeling of estrangement as Kafka did. His characters do not simply feel lonely. They feel exiled. From family. From institutions. From God. And even from themselves.

In The Trial, Josef K wakes up to find himself arrested. He is never told why. He spends the rest of the novel wandering through shadowy corridors of justice, seeking answers that never come. The world around him is familiar yet distorted. The people he meets are cold, evasive, or resigned. He is never given clarity, only confusion.

This is not just a nightmare of bureaucracy. It is the experience of being a human being in the modern world. Of feeling watched but never seen. Of crying out and hearing only the echo. Kafka does not exaggerate. He distills the silent scream of the soul in a world that no longer speaks our language.

In The Castle, K the land surveyor arrives in a village dominated by a mysterious castle. He tries to gain access. To find purpose. To be recognized. But every step forward leads to more confusion. He receives contradictory instructions. He meets people who talk in riddles. The more he seeks understanding, the more it slips away.

This is the central condition Kafka explores: the human being trapped in a system he cannot understand. A system that promises meaning but offers only exhaustion.

One of Kafka’s most haunting ideas is that of guilt without clear wrongdoing. His characters are often accused, punished, or condemned—but they do not know why. This is not because they are innocent. It is because they inhabit a world where moral clarity has collapsed.

Kafka once said, “The state we find ourselves in is sinful, quite independent of guilt.” This idea comes alive in The Trial, where Josef K insists on his innocence. But he is slowly crushed by a force he cannot resist. A force that reflects his inner fear more than any objective crime.

Kafka’s characters carry a guilt that feels inherited, existential, even sacred. It is not the guilt of a single act, but the weight of being human. They feel unworthy of love, of justice, of grace. This is not self-pity. It is the deep cry of the soul that longs for forgiveness, even when it does not know what it has done.

The Absence of God and the Longing for Grace

Kafka was deeply influenced by Judaism, but his relationship to God was marked by silence. Not the silence of atheism, but the silence of unanswered prayer.

His God is not absent in the sense of being unreal. He is present in the very structure of longing. But He does not speak. He does not explain. He remains just out of reach.

In one of Kafka’s parables, Before the Law, a man seeks entry to the Law. A doorkeeper tells him he cannot enter now, but perhaps later. The man waits his whole life. At the end, he asks why no one else came. The doorkeeper tells him, “This door was meant only for you. Now I am going to close it.”

This short story contains the heart of Kafka’s spiritual vision. We wait for something—truth, justice, God—but we do not know how to reach it. And yet, the waiting itself becomes our life. The struggle to find meaning, even in silence, is what makes us human.

In The Metamorphosis, Gregor Samsa wakes up as an insect. He is no longer recognized as a son or a worker. His voice is no longer understood. His needs are treated as burdens. His family slowly turns from pity to disgust. Eventually, they wish for his death. And he dies alone, unnoticed.

What does this grotesque transformation mean? Kafka never explains. That is his genius. We are left to interpret. And what we feel, more than anything, is that Gregor’s story is not fantasy. It is a terrifying metaphor for the way people are dehumanized when they no longer fit their roles.

Kafka shows how quickly love fades when we are no longer useful. How fragile our identity is. How easily we become invisible. The absurdity is not in turning into a bug. It is in how normal the world’s cruelty feels once that happens.

Despite the bleakness of Kafka’s stories, he is not a prophet of despair. His characters often continue to hope, even when all signs tell them not to. They write letters. They climb staircases. They argue their case. They knock on closed doors. Why?

Because something in them refuses to die. Some longing, some memory of meaning, drives them forward. Kafka once said, “There is hope, but not for us.” It sounds cruel. But it is honest. He is not rejecting hope. He is showing that true hope does not depend on success. It exists in the trying, not the result.

In this way, Kafka touches something sacred. His characters may not reach the castle, or the law, or salvation. But they keep going. And in that persistence, there is dignity.

Kafka’s prose is deceptively plain. He does not use elaborate metaphors. He does not describe emotions. He shows actions. He lets silence do the work.

His worlds are filled with corridors, doors, windows, staircases. His images are not decorative. They are symbolic. The castle is unreachable truth. The insect is alienation. The trial is judgment without clarity. His genius lies in making the abstract feel immediate. You do not analyze Kafka. You feel him in your chest.

Kafka Today: Why He Still Matters

In our time, Kafka’s vision has become more relevant than ever. In a world ruled by algorithms, faceless systems, and endless paperwork, we often feel like Josef K—judged, watched, but never truly seen.

The feeling of being caught in machinery, of speaking but not being heard, of longing for justice in a system too vast to understand—these are no longer just philosophical. They are everyday experiences.

Kafka gives no solutions. He offers no programs. What he offers is a mirror. A mirror that shows us our alienation. But also our endurance. Our absurdity. But also our stubborn hope.

Kafka’s Eternal Vigil

Franz Kafka stands at the edge of modernity. He does not turn away from it. He looks into it. And he shows us the human cost of progress without meaning. He teaches us that the soul does not disappear. It suffers. It questions. It dreams.

He believed that even in silence, we must seek. Even in absurdity, we must act. Even in alienation, we must love. His philosophy is not a solution. It is a stance. A quiet, trembling affirmation of the soul in a world that no longer believes in it.

Kafka reminds us that the greatest human courage may be not in conquering, but in continuing. In writing, even when unread. In praying, even when unheard. In knocking, even when the door does not open.

Kafka’s philosophy is not written in slogans. It is etched into quiet desperation. Into faceless corridors. Into unnamed guilt. He does not ask us to change the world. He asks us to notice it. To notice how absurd, how silent, how strangely sacred it still is.

Kafka does not give us meaning. He gives us the courage to ask where it went.

I simply desired to appreciate you yet again. I am not sure what I could possibly have sorted out in the absence of those tips and hints revealed by you on such a question. It became the challenging crisis for me, but being able to see your skilled tactic you processed the issue took me to cry over delight. I am just grateful for this information and wish you find out what a great job you are always putting in instructing people today all through your webpage. Most probably you have never met all of us.

you have got an awesome weblog here! would you wish to make some invite posts on my weblog?

I’m not that much of a online reader to be honest but your blogs really nice, keep it up! I’ll go ahead and bookmark your website to come back later on. All the best